In what ways do practices of the Quantified Self reshape understandings and experiences of the body and its functions?

1.Introduction

The fast growing technologies have changed our life in every aspects which includes our health and fitness management. Nowadays, the wearable technologies have been applied for individuals to do self-tracking on their own. Therefore, the Quantified Self movement appears and tries to establish ‘a relation between the body and the self, biology and knowledge, technology and truths’ (Ajana, 2017, p.4). The understanding of the body is reshaped due to the quantification and datafication by the technologies. Throughout the understanding process of the body, Lupton (2016) says that ‘the body and the self are enacted and reconfigured’. The aim of self-tracking process is to acquire knowledge of the body in order to improve it to a better version, which is about enhancement and improvement. This essay will develop analysis based on the body as a site of knowledge and power, discussing the implications of self-tracking data, biopower and biopolitics, and the neoliberal Self Quantifier. The discussion will base on the case study of 10,000 steps a day, WeRun online community and Apple ResearchKit and CareKit.

2. What is the Quantified Self?

The ‘Quantified Self’ website, founded in 2007 by Gary Wolf and Kevin Kelly, is a online forum where people can share their self-tracking experience and methods in a global range across thirty-four countries and the mantra is ‘self knowledge through numbers’ (Ajana, 2017, p.2; Quantified Self, 2019). Deborah Lupton defines the Quantified Self as ‘a means of monitoring and measuring elements of everyday life’ by using ‘mobile and wearable digital devices’ and ‘sensing technologies’ to acquire feedback in the form of digital data (Lupton 2016, p.3; Ajana, 2017, p.2). According to Swan, the Quantified Self tracking categories include ‘biological, physical, behavioural, or environmental information’ where any individual participates into tracking self (Swan, 2013, p.85). One of the areas that self-tracking applications focus on is health. Some of trackers use self-tracking devices to collect information about themselves and record their daily lives, and others collect specific information base on specific goals such as physical fitness, wellbeing and health, in order to draw their current body patterns and process further improvement to achieve better health condition (Lupton, 2016). Quantified Self reshapes understandings of health, therefore, reshapes people’s understandings of the body and health.

From a philosophical point of view, Cartesim dualism places body and mind separately as two different entities, where the body is ‘the location of a fixed sets of physiological processes’ and mind is ‘the location of thought’ (Blackman, 2008, p.4). However, the Quantified Self challenges the body as ‘a site a knowledge’ and controls the mind firmly (Ajana, 2017, p.5). Ajana (2017, p.5) points out that the body is both ‘a site of knowledge’ and ‘a site of power’. As people have great desire of knowledge, the Quantified Self provides technically supported access for understanding knowledge of the body through data.

3. Body is a site of knowledge

The technological generated data is the knowledge which reflects ‘biological functions and behaviour’ of the body and reshapes understanding of the body by computational implication (Ajana, 2017, p.5; Gilmore, 2016, p.2526). It means the Quantified Self urges people to understand an increasing quantified body through data. Therefore, the objective of the Quantified Self for individuals is to acknowledge the facts of the body, gain ‘a profound sense of self-awareness’ and acquire healthier life through improvement of the body (Quantid, 2019 cited in Ajana, 2017, p.5).

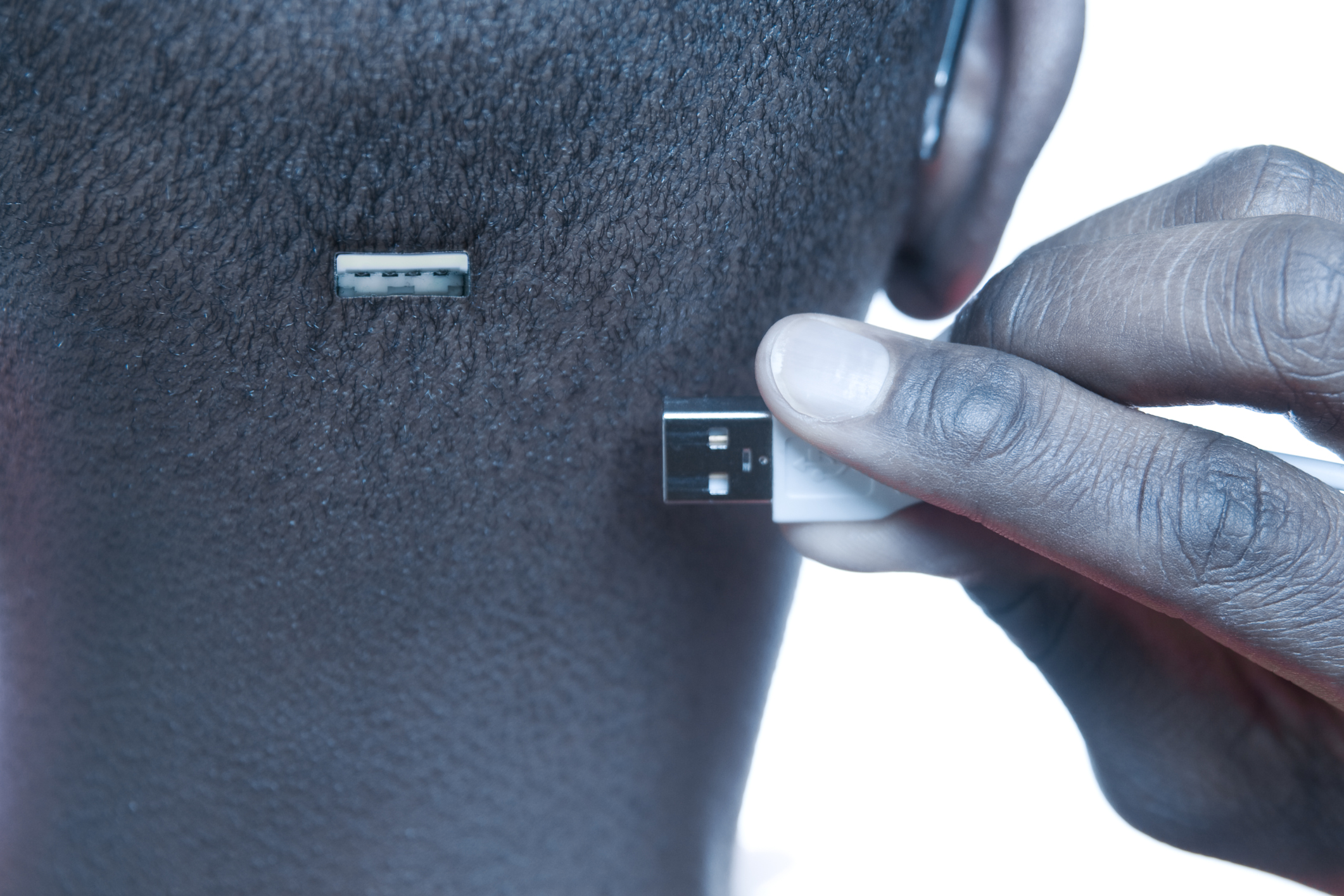

As I mentioned above, one of the aims of gaining knowledge of the body refers to self enhancement through the Quantified Self technologies. As the Quantified Self make people to understand the body through quantified biometric information, the body/self is treated as a form of cyborg which encloses a metaphor of the body/self as ‘a machine-like entity’ with ‘inputs’ and ‘outputs’ (Lupton, 2016, p.69). This viewpoint reflects a violation of ‘human/machine distinction’ by Donna Haraway (Hayles, 1999, p.84), indicating a merge between ‘cybernetics device and biological organism’ which means a merge between the Quantified Self technologies and the body/self. Besides, Hayles (1999, p.84) demonstrates the characteristic of cybernetics system as an assemblage of ‘flow of information. The Quantified Self technologies and the body and the self, share a same cybernetics system, which means they share same body data. Therefore, the body is data, and the data is the body and the self. Wolf does not believe in human beings due to the fallibility of a lack of precise information and awareness of themselves (Hille, 2019). He believes that data reflects the facts of the body and the self as ‘data doesn’t lie’, and the technical mediated attempts are able to help human beings to know body and its function in a more trackable way (Quantid, 2019 cited in Ajana, 2017, P.5; Wolf, 2019a). He treats the body and the self as a collection of data, and the body could be improved as same as updating a system of machine due to quantification and datafication.

3.1 The body is a collection of data

The way we learn the body is shifting from qualitative to quantitative (Gilmore, 2016). Everywear, the wearable fitness technology as an utilisation of the Quantified Self, is used by Adam Greenfield to describe a ubiquitous technology which penetrates everyday spaces, aims to track and quantify experience and movement of the body (Greenfield, 2006 cited in Gilmore, 2016; Gilmore, 2016). Any of a wearable sensor which records calories, number of footsteps, walking and running distance, heart rate and any other biometric readings of the body, could be understood as ‘a datafication of the body’ (Mayer-Schonberger and Cukier, 2013, p.48 in Gilmore, 2016, p. 2525). As Greenfield stated that ‘everywear acts at the scale of the body’, therefore, the body may be given more computational implications as the being of self is countable through quantification (Greenfield 2006, p.48; Gilmore, 2016, p.2526). For example, footsteps have both qualitative and quantitative meaning. Based on De Certeau’s notion of footsteps, the act of walking in the city makes footsteps as ‘a unique form of moving through space’, hence, each step is given qualitative nature and countless (De Certeau 1984, p.97 cited in Gilmore, 2016). The Quantified Self reshapes the qualitative implication of footsteps. Instead, they exists as a form of data. Fitbit (2019) published a blog article online which tried to demonstrate that walk 10,000 steps a day can satisfy any individual’s daily goal of thirty minutes of activity in order to help reduce the risk for disease and stay healthy. In this case, footsteps are altered into numbers which are stored as form of digital data, calculated to measure health condition of an individual. The users are allowed to learn their bodies and health condition through reading the digital data.

However, to read the numbers of one’s footsteps does not equal to gain knowledge of the body. Although the numbers are the facts of the body, ways of interpretation of data decide how to understand the facts. People may not care much about the numbers. What they intend to know is their health condition which the data implies. When you go to a hospital to do a physical examination, doctors make diagnose to inform your state of health. Hence, what you can know about your health depends on how doctors analyse and interpret your results which reflect physical readings of your body. Self-tracking devices are tools for monitoring, but have no data interpretation ability. The Fitbit blog (2019) refers the Japanese marketing campaign’s usage of 10,000 steps, the suggestions from so called ‘medical expert around the world’, as well as a journal article (Scherrer et al., 2010) to support why they set 10,000 steps as a default daily objective for each user. These evidence are irrelevant to support from neither medical nor academic perspective, as the journal article discusses that in what extent the corporate physical activity programs influence productivity of employees in the workplace (Scherrer et al., 2010), while the Fitbit blog aims to persuade users to accept their marketing strategy, rather than truly prove the benefits of 10,000 steps a day for health. Therefore, if the 10,000 steps are interpreted as a standard for maintaining health, then the users could believe that this reading is the facts of the body. In this case, the facts of the body are reshaped by business for certain aims, such as marketing and promotion. Who owns the ability to interpret data, who would actually control individuals to understand their bodies. Data could not tell people the truth unless they are given discourses/interpretations.

On the other hand, to be a machine-like entity does not equal to be an operational system which can be precisely updated to an ideal form or state. Further, to gain ‘output’ does not mean to gain the key towards self enhancement. The ‘Cyborgian human-technical co-control’ extends power of control from both societal and technical control (Hille, 2019). As the body/self is containment of digital data which is demonstrated by liquid entities, therefore, the discussion about control of self is not only about controlling the body by using data, but also controlling the data (Lupton, 2016, p.89). In social context, it could mean the society exerts more power of control over health, and to be more productive in the workplace. For the data, it could refer to privacy issues, including data access and data ownership.

4. Body is a site of power

The discussion of the body as a site of power should focus on how is the power of control entered on the self. Ajana (2017, p.5) thinks that ‘a desire for control’ is the core incentive of the Quantified Self movement. The Quantified Self exerts ubiquitous control over the body and its functions. Power only ties up the control of population activities and penetrates into our lives in a more reasonable and rigorous way. For example, demographics and surveys gain the right to enter personal life, and the resulting analysis Data and models can also establish population activities. Hille (2019) points out that the Quantified Self is at the intersection of ‘self and external control’, ‘ the objectification of the self’ and ‘regulation in accordance with social norms of health’. ‘For knowledge, as Francis Bacon reminds us, is power’ (Ajana, 2017, p.5). Therefore, the control also refers to the mastery of self-knowledge, in other words, the mastery of one’s biometric data.

4.1 The control by biopower and biopolitics.

Michel Foucault (1928, 2003, 2009, 2010 cited in Ajana, 2017, p. 5) describes biopower as a form of power which is exerted on body of the individual and the population which tries to penetrate into the order of society, taking ‘biological existence of population’ and ‘vitality of the body’. Biopolitics is defined as a political force which incites the optimisation of individual’s physical body, ability and productivity for regulation of the subject (Hille, 2019). The control starts with understanding the body and the self (Hille, 2019). Therefore, through the Quantified Self, the biopolitics control is exerted on the body and the self by a more powerful way.

The control is presented by social norms of health. Here, the discussion can be followed by WeRun as an example. WeRun is a digital pedometer application which is built in WeChat, a very popular social media platform in China. Users have their own WeRun community which is constructed based on users’ own social networks in WeChat. WeRun gathers the number of steps from all of your friends who enable WeRun to gain access to their footsteps data. The sources of number of steps are from users’s devices built-in health and fitness app such as Apple health. Everyday, each user’s number of steps will be counted and formed the ranking which will be published from the highest to the lowest, and every user in a same community is able to check the ranking. Hence, ranking function is set out to trigger a competition, which provides a new function of social networking, moreover, evokes motivations between users.

Cialdini, Reno, and Callgren (1990 cited in McFerran 2015) demonstrate two types fo norms, which are descriptive norms and injunctive norms. The former one indicates what others do most, the latter one indicates what others think as positive or negative (Cialdini, Reno, and Callgren, 1990 cited in McFerran 2015). For example, a descriptive norm can be most users of WeRun believe in 10,000 steps a day and execute it in everyday life. Then the inductive norm can be these users think the more number of steps means to achieve better health and fitness.

In fact, WeRun successfully play 10,000 steps a day apply to its individual users and communities. Communities even persuade their users to walk much more than 10,000 steps, which implies two meanings: first, if 10,000 steps is a daily basic needs of keeping healthy, then the more a user walk, the healthier the user will be; second, it does not matter how many steps a user walks, it matters how many steps the other users from the same community walk. As a result, the community is able to manipulates norms of health based on 10,000 steps a day, and ties up users to WeRun and their communities in order to let them keep using it until it becomes daily routines.

WeRun creates some methods to make users comply with social norms of health and fitness, by which means 10,000 steps a day. Foucault (1976, 2003, 2009, 2010 cited in Ajana, 2017, p.5) points out that biopower and biopolitics are ‘normalisation and control in the name of freedom itself’. Nonetheless, it is argued that individuals still have power to reject the social norms of health which takes the individuals dislike and do not intend to be associated (NcFerran, Dahl, Fitzsimons, & Morales, 2010a, 2010b; White & Dahl, 2006, 2007 cited in McFerran, 2015). But it may difficult for users not to be influenced and changed because the quantification of the body is ubiquitous, and any WeRun community tries to create a health monitoring environment which always try hard to engage users as much as possible.

Firstly, WeRun takes advantage of user’s empathy. For example, it ties up philanthropic projects with 10,000 footsteps a day. WeRun encourages users to donate their footsteps in order to plant trees in desserts, or donate bottle milks for children in need. On the page of processing donations, WeRun only allows users who achieve the goal of 10,000 steps a day to participate in donations, It does not explain the reason but emphases the health benefits of walking 10,000 steps daily, which is literally like what Fitbit (2019) blog states. This phenomenon could be taken to a forceful engagement of health, although it does not point out any reasonable relations between this philanthropic project and personal health and fitness. Therefore, it exerts biopower and biopolitics control over individual’s biological health in the name of freedom. Although it seems like to offer users freedom of whether participate to any philanthropic project, but actually implies the coercive discipline.

To create higher user engagement could be one of the objectives which WeRun tries to achieve. It is not only for making benefits, but also implies a series of methods to tie the users and their bodies up to social norms of health. WeRun controls and reshape bodily health experience by habitualisation. Every day, the ranking informs users to take part in 10,000 steps a day. The competitive WeRun community environment is like catalyst, such as the ‘likes’ from other people can motivate users to keeping walking at least 10,000 step and shows better performance to the fellows. Therefore, when users are get used to be informed by ranking and motivated by other users every day, they are very likely to keep performing, hence, walking 10,000 steps could become their daily habits although it is for satisfying themselves by impressing others. Gilmore (2016, p.2525) points out that the body is tied up by everywear technologies by habitualisation. As WeRun based on social media, the norms of health is more easily to be broadcasted. Meanwhile, the act of self-tracking is watched, monitored, compared and shaped within each other in WeRun communities. Therefore, the control of the body and the self is more easily to be exerted over individuals and groups of individuals.

The social norms of health make individuals believe that they are healthy only if they obey such norms and do what the most others do, therefore, they are actually governed by themselves rather than specific social rules or laws. A society of control governs any individual by the self instead of laws (Gilmore, 2016). Social norms of health increases likelihood of bodies by social norms of health by optimisation, making bodies fit into social norms of health, hence, reducing the uniqueness of each body. Moreover, due to such similarities of bodies, ‘the everyday life of at risk bodies becomes predicted on issues of power and control’ (Gilmore, 2016, p. 2530).

4.2 A neoliberal attitude towards the Quantified Self

A neoliberal attitude towards the Quantified Self refers to individuals who ‘voluntarily monitors, measures, regulates and collects biometric data on their own health, wellbeing and fitness, taking control of their own bodies’ (De Souza, 2016 cited in Ajana, 2017, p. 4). It means self-tracking should base on a voluntarily attitude towards the data, including the

access of data and the ownership of data. Lupton (2016, p.89) argues that one of the discourse of control is about ‘exerting control over the data themselves’. As the body is a site of knowledge and the knowledge is biometric data in the context of the Quantified Self, data privacy could link to the mastery of self-knowledge, which means who can control the self-tracking data by owning the data and the data access, who is able to gain mastery of the knowledge.

Apple tries to build an ecology which allows users to voluntarily engage in health monitoring, interpretation and self-management. It believes the optimistic use of Quantified Self technologies and aims to benefit individuals and the society on healthcare through engaging a wider range of participants to share their data. Apple ResearchKit and CareKit are two software frameworks for apps which aim to improve medical research and medical conditions management based on open source, hence, Apple asks for amount of data as much as possible from the users in order to build more accurate database (Apple, 2019). The important factor which should be noticed is the open source framework of building these apps, which means that everyone is able to donate their data and gain access of data from others and their own. It makes self-tracking is not a personal affair anymore but a data philanthropy. Data philanthropy is the belief that it is beneficial to share data for the public. As Ajana demonstrates, here, a participatory model of health management is stimulated, and a mind-set of ‘personalised preventive health maintenance is formed’ (Ajana, 2017, p. 5).

On the other hand, this case could be referred to a shift from the Quantified Self to the ‘Quantified Us’ , as well as a shift from regulation of the self to the regulation of the population (Ajana, 2017, p.10). It transforms the biopolitics from the micro to the macro level, which means the control towards the individuals is expanded towards a large population (Ajana, 2017, p. 10). However, as De Souza (2016 cited in Ajana, 2017, p.7) suggests that the neoliberal self-quantifier can voluntarily make choices about what and how to use biometric data, and decide what information that users want to provide and which apps. Furthermore, these shared data is always visible to the providers. Users always concern about if their data could be used by companies for marketing strategies, which treats data as products in order to make benefits. The same concern could be applied to Apple. Apple promises users that they are in charge of their data, which means they are able to control others and their own access of data (Apple, 2019). The settings allows users to set which apps can access to their biometric data. As a result, users own their privacy of personal health data, which means they own the mastery of health data as self-tracking knowledge. Therefore, Apple empowers the users by owning the data itself, learning form the data to picture their health condition.

5. Conclusion

In general, the Quantified Self movement brings new opportunities on tracking health by wearing sensors which allows individuals to know their body and health patterns individually through data. The users do not need to rely on institutions to gain bodily knowledge and experience, but can know it through reading their own data anytime and anywhere. Users are empowered to control their bodies and knowledge. Therefore,

the body and knowledge become two important things which refers to discussions of power of control from technologies, the society and users themselves. The biopower and biopolitics, and the neoliberal attitude towards the Quantified Self are two different perspectives of the relations between the Quantified Self, the body and the external control from the society. They all implies that the understanding of the body, can be reshaped by the Quantified Self movement.

Human beings are not just satisfied with being controlled or to control the body, rather, they are trying to reach a higher standard which probably aims to modify a perfect biological body. Therefore, the way that we use technologies for self enhancement is another serious question should be discussed further. As Wolf comments on the Quantified Self website’s open forum that ‘our role is not to sell this technology to ourselves, but to use it thoughtfully and share our knowledge, so that we add reflective capacity - that is, some thoughtfulness - to the systems we and others are making’ (Wolf, 2013). Ideally, the Quantified Self technology can help individuals explore, understand and share the truths of the body as an optimistic tool rather than a product of power and control.

Bibliography

Ajana, B. (2017). Digital health and the biopolitics of the Quantified Self. DIGITAL HEALTH, 3, p.205520761668950.

Apple (United Kingdom). (2019). ResearchKit and CareKit. [online] Available at: https://www.apple.com/uk/researchkit/ [Accessed 2 May 2019].

Fitbit Blog. (2019). The Magic of 10,000 Steps - Fitbit Blog. [online] Available at: https://blog.fitbit.com/the-magic-of-10000-steps/ [Accessed 2 May 2019].

Gilmore, J. (2016). Everywear: The quantified self and wearable fitness technologies. New Media & Society, 18(11), pp.2524-2539.

Greenfield A (2006) Everyware: The Dawning Age of Ubiquitous Computing. Berkeley, CA: New Riders.

Hayles, N. Katherine. (1999) How we became posthuman: virtual bodies in cybernetics, literature, and informatics. Chicago, Ill. : University of Chicago Press.

Hille, L. (2019). The Quantified Self - Ubiquitous control [online] Available at: http://www.digital-development-debates.org/issue-16-food-farming--trend--the-quantified-self-ubiquitous-control.html [Accessed 2 May 2019].

Lupton, D. (2016). The Quantified Self. Polity.

Quantified Self. (2019). Quantified Self. [online] Available at: https://quantifiedself.com/ [Accessed 2 May 2019].

Scherrer, P., Sheridan, L,. Sibson, R., Ryan, M., and Henley, N., (2010) Employee Engagement with a Corporate Physical Activity Program: The Global Corporate Challenge. International Journal of Business Studies: A Publication of the Faculty of Business Administration, Edith Cowan University, Vol. 18, No. 1, 2010: 125-139.

Swan, M. (2013). The Quantified Self: Fundamental Disruption in Big Data Science and Biological Discovery. Big Data, 1(2), pp.85-99.

Wolf, G. (2013) Photo-Life-Logging Experiment at the QS Conference. [Online] Available at: https://forum.quantifiedself.com/t/photo-life-logging-experiment-at-the-qs-conference/587 [Accessed 25 April 2019]

Wolf, G. (2019). The Data-Driven Life. [online] Available at: https://www.nytimes.com/2010/05/02/magazine/02self-measurement-t.html?_r=0 [Accessed 2 May 2019].